Urban populations are rising rapidly: by 2030 over 90% of the UK’s population is expected to be living in urban environments. Cities are improving or replacing ageing infrastructure and systems to respond to this demographic evolution, to maintain core services and create new ways to support a tech-savvy population.

Smart cities are real

Smart cities may be the latest byword after big data and the internet of things, but this is not a futuristic concept that could be reality in a decade’s time: the future is already here. Almost every one of us walks around with a smart phone in our pocket: we use them to adjust our home thermostat on our daily commute and view live data on traffic congestion or public transport before leaving the office. We live in a smart world and we expect services and information in real time.

Real smart city projects are already running across the country, exploring how to bring together the strands of smart technology to create smart cities with the ultimate aim of enhancing the scope and performance of urban services, to reduce resource use and engage with citizens.

The lamp post’s role

The lamp post is quite literally well positioned to play a leading role in smart cities. As a central piece of city infrastructure, the major opportunity facing our industry is the chance to develop technology that will help achieve the aims of smart cities and truly engage residents, businesses and communities.

Smart technology is already being developed for lamp posts, from air pollution sensors to parking meters. However, to truly create smart cities (and not scientific experiments) it is paramount that the solutions are valuable enough for communities to adopt them and use them in their daily lives. For engineers and designers, that means taking a “bottom up” approach to developing technology: the best smart city solutions will be citizen-centric, producing use cases that create more efficient ways of doing things, or providing improved services to residents and businesses. That can only be achieved if the community understands what the smart city is trying to accomplish, and engages with the technology.

In Glasgow’s smart city project, the brightness of street lighting automatically adjusts from 40% to 100% when a passing pedestrian or cyclist is detected, increasing safety (a clear benefit to residents) whilst also reducing energy costs. In contrast, the City of London rejected plans to allow smart bins to collect footfall data because of “Big Brother” fears the rationale and benefits of such technology failed to counter concerns around privacy: data collection alone was not a strong enough incentive.

Connecting Communities

Engaging residents and businesses may be the job of public officials, but community-centric use cases are essential if they are to be viable. In a climate of spending reviews, squeezed budgets and tough competition for funding, only the most desirable use cases that deliver high benefits and commercial sustainability will be adopted.

This is where industry must take the lead: not just in developing technology that improves services or achieves greater efficiency, but by creating solutions able to deliver benefit beyond their operational costs, and that continue once the project funding has been spent. This will mean that street lighting and lamp posts remain core to city infrastructure, not overtaken by other competing technology. In achieving cost efficiency, the battle is already half won: adapting existing infrastructure is almost certainly a cheaper alternative to installing and implementing new options.

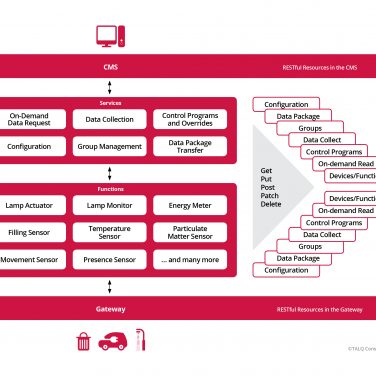

Whilst monetising solutions will be crucial, the real key to adapting city lighting infrastructure to facilitate smart cities will be greater interoperability. Like many current services, street lighting can be guilty of working in silos: Lucy Zodion’s Vizion® Central Management System (CMS) is one of only a few CMS fully compatible with other systems. In addition the new Ki. platform is open and interoperable with various software and hardware, for complete control and enhanced insight generation; it transforms the lamp post into a hub of communication, able to gather and aggregate various datasets from smart devices that have been installed among it.

Yet smart technology requires that systems communicate with each other freely, sharing information and data to create intelligent solutions beyond one individual technology or function. With limited budgets, councils may also expect technology that will seamlessly integrate with legacy systems without the funds to invest in whole new infrastructure projects: a gradual shift towards a smarter city rather than an overnight revolution is far more likely.

Interoperability in street lighting

Interoperability will of course present some challenges in itself achieving integration on open protocols whilst maintaining security where required will be essential. This can be overcome: as with anything, once something is required, solutions to overcome any barriers to it will be identified. Security can be adapted to enable greater protection for control commands than sensor data. Privacy can be maintained without blocking interconnectedness. What’s more, the very key to smart cities will be collaboration working with multiple partners, providers and parties to create solutions that encompass different technologies and use cases.

Our industry will play a key role in moving smart cities to reality. We must educate and create viable use cases that inspire both councils and private enterprises to invest and implement smart lighting technology as an integral part of smart cities. We must collaborate and deliver solutions in true partnership to ensure the unassuming lamp post continues its central role in the city of the future.